Feb 2024 - Present

Supervisors: Prof. Hanna Kokko

Ageing, or senescence, is the phenomenon of mortality rates of organisms increasing through the course of their lives. Despite senescence having obvious negative fitness consequences (such as death), it is nevertheless a fact of life that most organisms age. Why doesn't natural selection lead to ever-increasing lifespans? The 'developmental theory of aging' (DTA) suggests that aging evolves due to evolution prioritizing optimization of early-life fitness at the cost of fitness later in life (For example, see

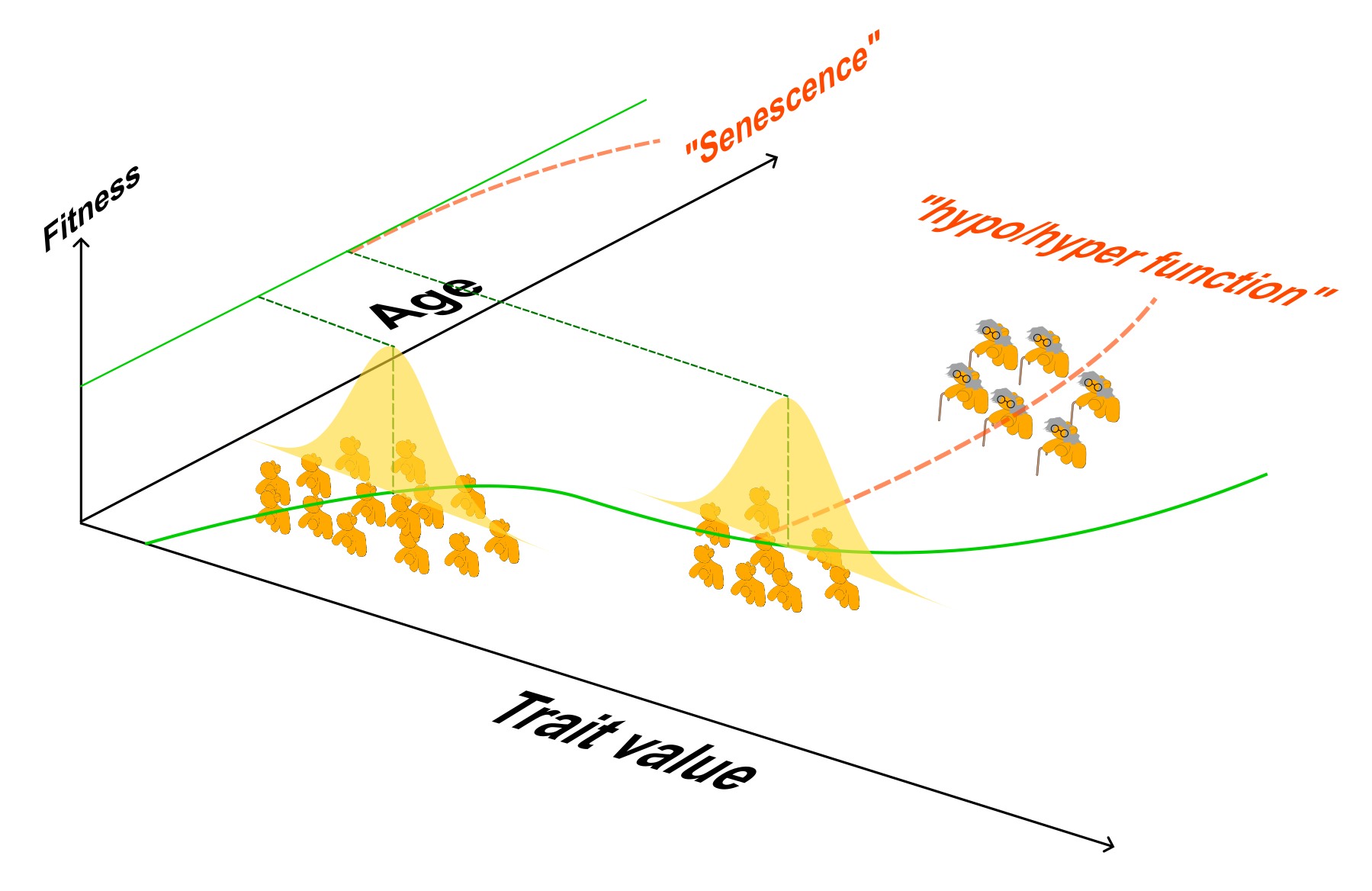

Lemaître et al. 2024). In other words, if the optimal value of a trait varies with age, the DTA posits that evolution favors optimality early in life even if this comes with a cost later in life. Aging in this framework is thus a consequence of failure to adapt to a changing optimum leading to either hypofunction or hyperfunction in gene regulation, which in turn leads to sub-optimal, and eventually catastrophic, organismal function. I am using tools from mathematical optimization theory and the calculus of variations to formalize this idea and examine when age-dependent optimal trait expression can lead to senescence. For instance, studies of aging routinely assume that selection is weaker later in life (the famous 'selection shadow'). Is a selection shadow really necessary for aging as envivionsed by the DTA? If so, how strong must this shadow be? If not, can aging evolve simply due to limited plasticity in trait expression?

A schematic depiction of the evolution of ageing as a result of hypofunction/hyperfuuction arising from failure to track a changing optimum.

At the proximate level, senescence can be more mechanistically understood via the accumulation of failures of various physiological processes required for organismal function. In this view, an organism is a complex system consisting of many interdependent sub-systems, each with some intrinsic risk of failure due to the vagaries of life. These sub-systems could be genes, organs, tissues, or something more abstract, such as cellular pathways, metabolic functions, or foraging ability. Crucially, in any such conceptualization, the functioning of each sub-part depends on the well-being of other sub-parts. For instance, a faulty heart places additional stresses on lung functioning. Thus, in general, failure begets failure and the failure rate of a sub-system depends on how many sub-systems have already failed. Organismal mortality then depend on the fraction of currently operational sub-parts. For my PhD, I am using mathematical models to study whether such interdependencies are sufficient to reproduce patterns of demographic senescence without invoking a selection shadow.

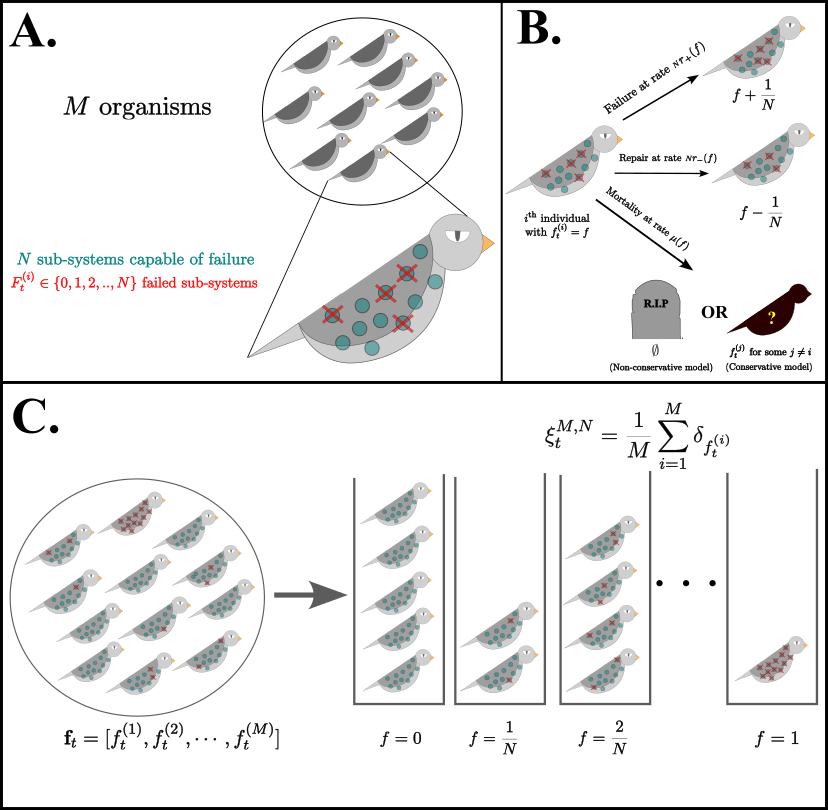

More specifically, I am working with models of the following form:

We begin with \(M\) independent, non-interacting organisms in a cohort. Each organism has \(N\) sub-systems capable of failure. Within the \(i\)th organism, \(F^{(i)}_t\), the number of failed sub-systems at time \(t\), follows a density-dependent birth-death process on \(\{0,1,2,\cdots,N\}\) with transition rates \(F^{(i)} \to F^{(i)} \pm 1 \textrm{ at rate } Nr_{\pm}(F/N)\), corresponding to stochastic failure amd repair of failed sub-systems. This defines the individual-level dynamics. At the population level, one of two variants are considered. In the non-conservative model, an individual with \(F \in \{0,1,2,..,N\}\) failures is chosen to die at rate \(\mu(F/N)\). Thus, the population-level dynamics consist of individuals disappearing from the population at a rate equal to their mortality hazard. In the conservative model, an individual chosen for death is instantaneously replaced by a copy of another individual, chosen uniformly at random from the population of \(M\) organisms, ensuring that the total population size remains constant. Thus, in the latter case, the population-level dynamics are described by a Moran process with selection and Death-birth updating. Inspired by ideas from multi-level selection theory, we can reframe this as a sub-probability measure-valued stochastic process with state variable

\[\xi^{M,N}_t(\cdot) = \frac{1}{M}\sum\limits_{i=1}^{M}\delta_{f^{(i)}_t}(\cdot)\] where \(f^{(i)}_t = F^{(i)}_t/N\) is a rescaled version of the individual-level process governing failure dynamics. The stochastic process \(\{\xi^{M,N}_t\}_{t \geq 0}\) tracks the proportion of individuals in the population having a proportion \(f = F/N\) failed sub-systems, and takes values in the space of sub-probability measures on \(\{0,\frac{1}{N},\frac{2}{N},\ldots,1\}\).

A description of a two level stochastic process for modelling mortality curves and senescence patterns. (A) The model consists of M organisms, each of which have N intra-organismal sub-systems capable of failure. (B) An organism with f = F/N failures may either accumulate another failure, repair a failed sub-system, or die. Death is either without replacement or with instantaneous replacement by another individual chosen uniformly at random from the population. (C) We characterise the population via a ball and urn scheme by counting the number of organisms that have f = F/N failures for each posssible value of f, and then dividing this number by the initial population size M.

If we first take \(M \to \infty\) (very large cohort size) and then use a diffusion approximation on \(N\) by neglecting terms of \(\mathcal{O}(N^{-2})\), it can be shown that the stochastic process \(\{\xi^{M,N}_t\}_{t \geq 0}\) converges to a deterministic measure \(P(f,t)\) described by the Fokker-Planck-Kolmogorov type PDE

\[\frac{\partial P(f,t)}{\partial t} = -\frac{\partial}{\partial f}\{r(f)P(f,t)\} + \frac{1}{2N}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial f^2}\{\tau(f)P(f,t)\} - \left(\mu(f) - \mathbb{1}_{R}\int\limits_0^1\mu(x)P(x,t)dx\right)P(f,t)\] where \(r(f) = r_{+}(f) - r_-(f), \tau(f) = r_{+}(f) + r_-(f)\), and \(\mathbb{1}_{R} = 1\) if we are considering the model with instantaneous replacement and 0 otherwise. The PDE is conservative in the former case and non-conservative in the latter. Interestingly, from a stochastic process perspective, the PDE above with \(\mathbb{1}_{R} = 0\) is precisely the Kolmogorov forward equation for a well-known stochastic process called diffusion with killing with instantaneous killing rate \(\mu\). The PDE with \(\mathbb{1}_{R} = 1\) describes the conditional probability density of this same stochastic process conditioned on non-absorption/survival. Furthermore, on biological grounds, we are able to argue that we often expect \(r(f)\) to take the form \(r(f) = \lambda(1-f)(\phi + kf)\) for positive constants \(\lambda, \phi, k\). Similar equations with \(\phi = k = 1\) appear in multi-level selection theory and the evolution of cooperation literature if we interpret mortality as a negative payoff. We are currently writing up much of these results as a manuscript.

I am interested in trying to more thoroughly understand how to translate known results between multi-level selection and the evolution of senescence using these PDEs. I am also interested in understanding the biological consequences of the fact that the conservative version of the PDE can both be interpreted as a deterministic model of an infinitely large population (as the scaling limit of the stochastic process above, as used in MLS) and as a stochastic model of a single individual with failure, repair, and mortality risk conditioned on survival of the individual (as arising from the generator of a diffusion with killing; similar things have been used in senescence/demography literature). I am currently trying to do this via Feynman-Kac techniques but overall remain somewhat befuddled.

There are also other obvious scaling limits of \(\{\xi^{M,N}_t\}_{t \geq 0}\) that are biologically interesting. For senescence, the most biologically pertinent limit is \(N \to \infty, M < \infty\) (very large number of sub-systems within each organism, limited cohort size), but in this limit, the process is a scary measure-valued branching process on the space of sub-probability measures on \([0,1]\) that I don’t really understand yet :(